Homeless in England

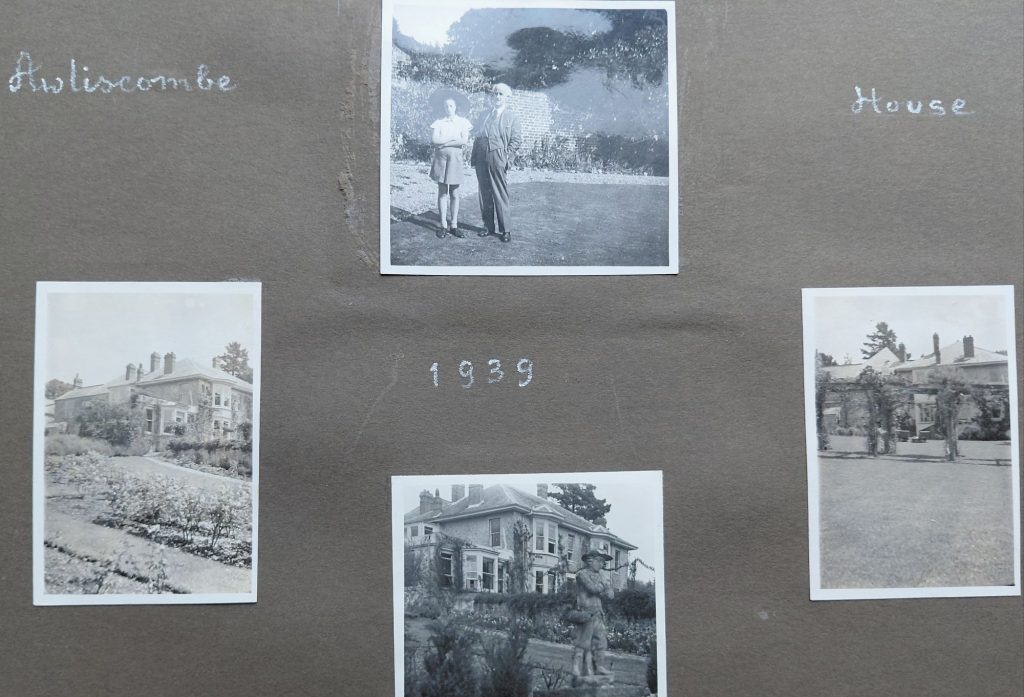

Once back in the UK, the little family needed a home. The houses in Midlothian had been sold. Arthur’s poor health and precarious financial situation meant that Scotland was not an option. So they rented, moving a couple of times until Lady Mary’s in-laws from her first marriage to Lt Commander John Codrington (killed in action in 1921) came to the rescue, providing a farmhouse in a Devon village, where they lived for the next five years.

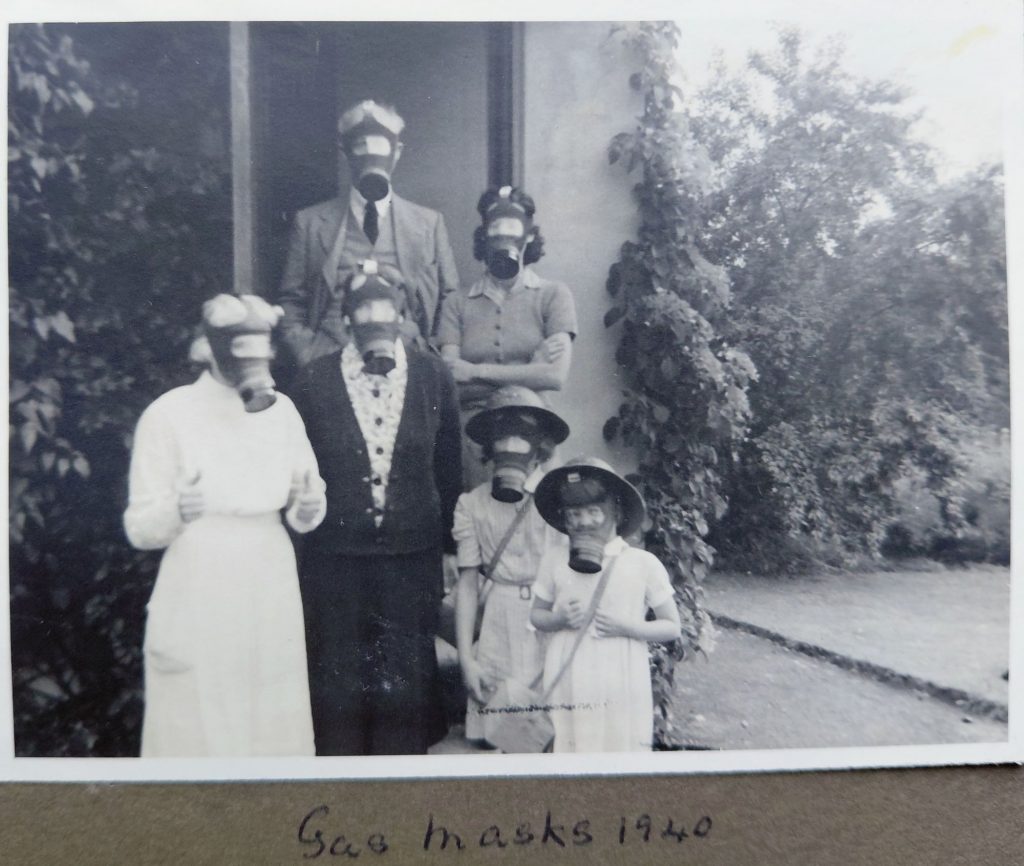

The girls could keep ponies, and attended Les Oiseaux, a convent school that had been evacuated from Westgate-on-Sea to Shropshire. Summer holidays on Exmoor enabled them to get away from the troops that were quartered in the stables at Awliscombe, while Arthur joined the East Devon Defence network, scanning the night skies for bomber raids. An evacuee family came to stay, and may be included in the photo below. Liz is the younger child.

As the older child, Euphan found herself running the house, cleaning and managing the ration books. Lady Mary had no housekeeping skills, and must somehow have retained a cook during the War, as no one in the family knew how to.

Travels in the 1930s

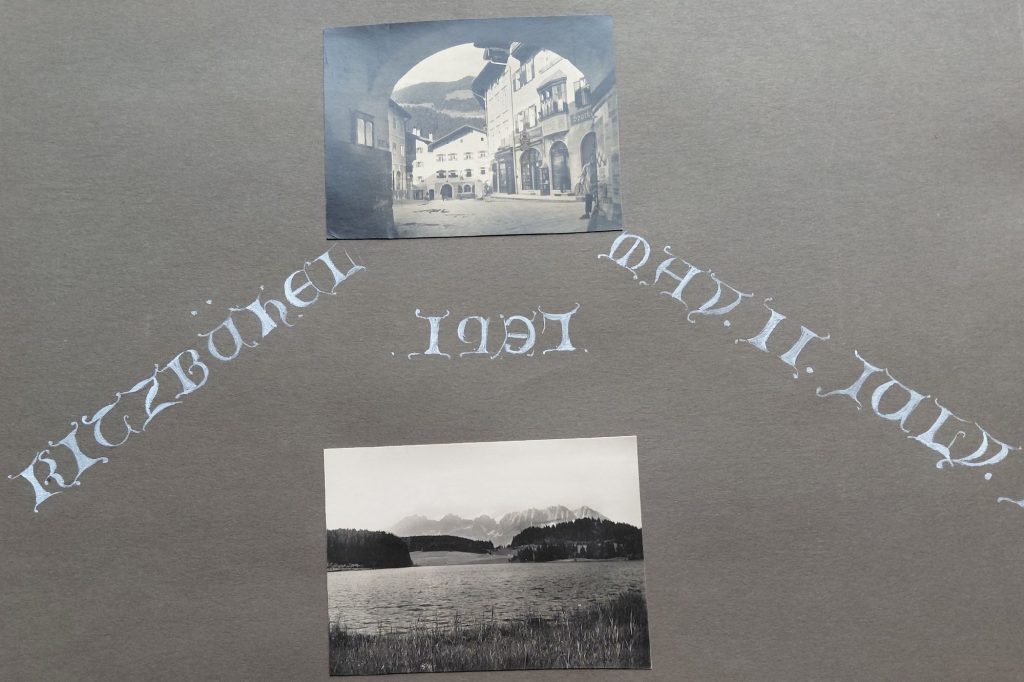

When Arthur Balcarres came home from the First World War, he was not a well man. Nevertheless, he married The Hon Mary Alexandra Fraser in 1928 and they lived in Tilliicoultry, where Euphan and Liz were born. With inherited debts and no income from the land, Arthur had no choice but to break the entail, sell the farms and put Whitehill House on the market. They moved to Kitzbuhl, a village in the Austrian mountains, in 1937. In that earthly paradise, the girls wore dirndls and played in the upland meadows. Erica came to visit, and Euphan made life-long friends with a little girl called Emma von Gutmannstahl Benevenuti, whose family had a summer chalet outside the village. The photos were taken by Mary and have been preserved in two albums.

The top photo catches Arthur playing with the girls at Tillicoultry, then we see him relaxing in a summer meadow with Liz, in the lower photo.

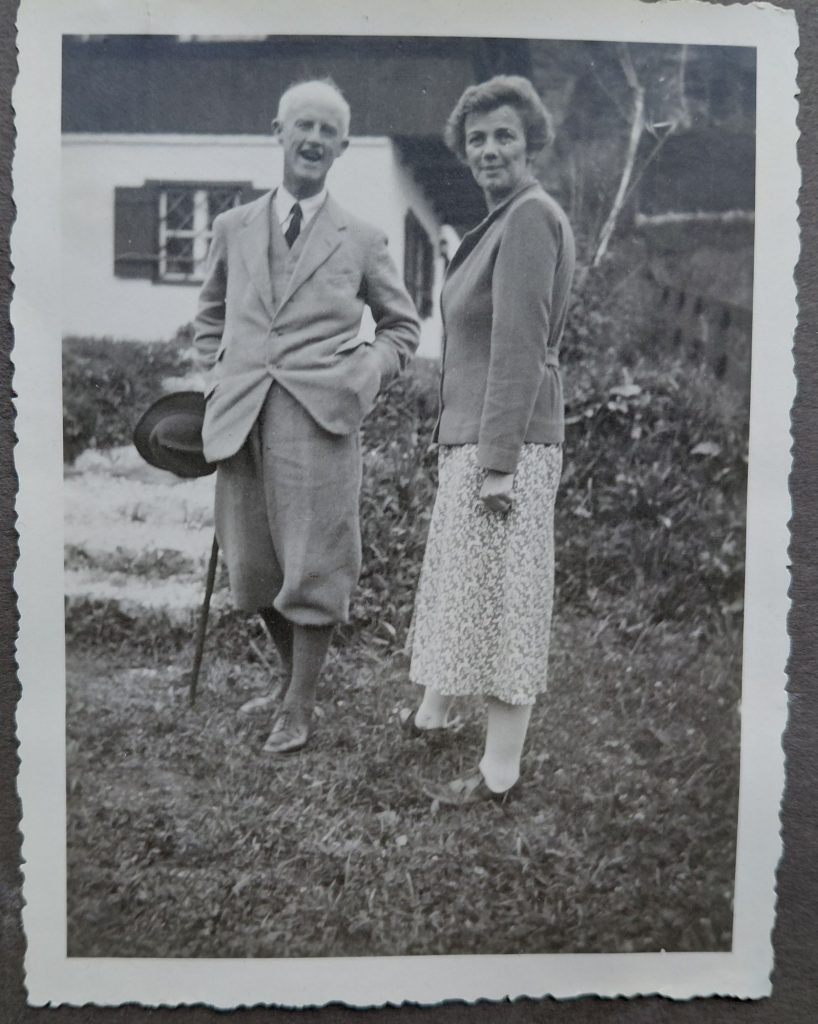

Would they have stayed? Friends and family came to visit: here’s a photo of Arthur’s sister Erica, enjoying the clean air.

Well, of course they had to come home when war was looming.

They said goodbye to Bonzi, and left Austria in 1939.

Celebrating the Hay connection

This gorgeous portrait by Daniel MacNee definitely shows her off as a cherished married woman, wife, wearing a lovely Paris outfit, and showing the ring on her finger as she toys with her eye-glasses. Her new home, Whitehill, lies in the distance, and she is sitting on an embroidered red shawl, another acquisition from their lengthy travels in Italy? Her face has a pre-Raphaelite air; they had been gazing at so many Madonnas!

Relatives?

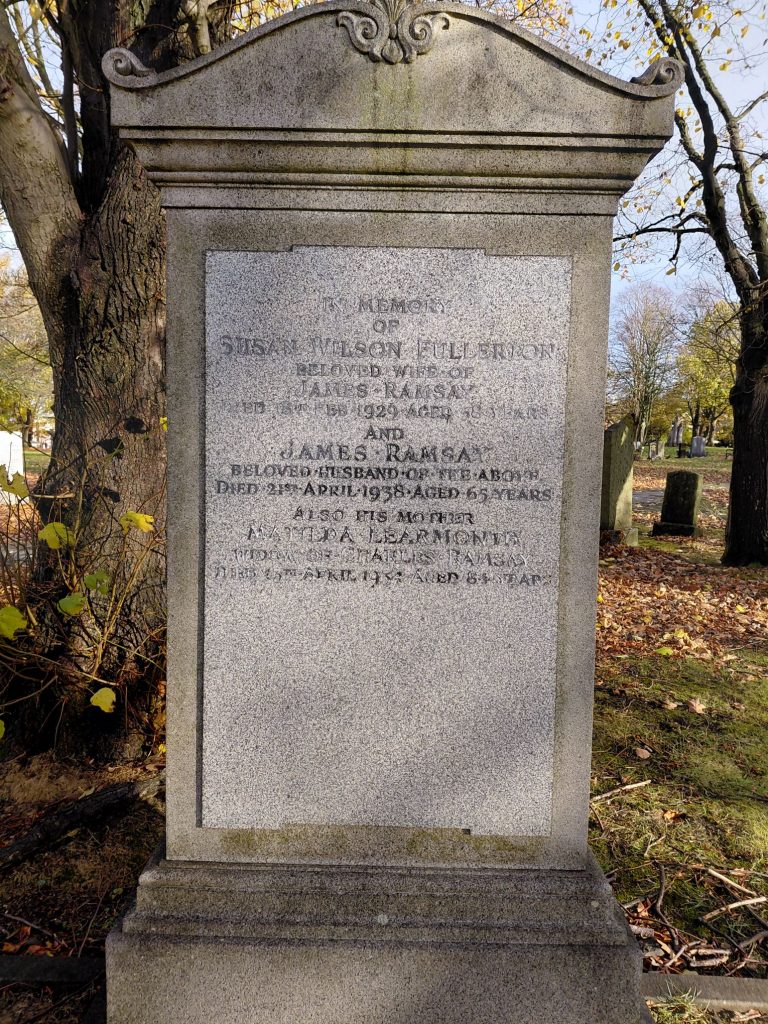

I’m always thrilled to spot gravestones that record Ramsays, and this one in Clermiston Cemetery does even better. The faded lettering refers to Matilda Learmonth, widow of Charles Ramsay. She died on 13 April 1934, aged 84. Hopefully her son James Ramsay was at her side. Scottish family names have a perennial quality, which can make research difficult! Do get in touch if you know about these Ramsays.

Who is this wee guy?

Seldom do we not know the names of male portraits, unlike female portraits whose identities are soon forgotten.Anyway, this miniature is clearly a momento for the child’s family, as he leaves to join the Army — or the Navy? Do his jacket buttons have a nautical air? His fair locks suggest a Wardlaw connection, so I’m tentatively suggesting it shows Wlliam Wardlaw as a boy, on his way to Portsmouth, to join the East India Company. Maybe!

Who is he?

Sir Henry Wardlaw

Arthur Balcarres Wardlaw Ramsay was apparently taken back to discover that his Wardlaw ancestors had been far more eminent than the Ramsays whose papers he was so keen to preserve. Eminent as Sir Henry Wardlaw had been as Chamberlain to Queen Anne, and proud to be created a Baron of Nova Scotia by Charles I, his line died out in the fourth generation when it ran out of male heirs. Indeed, on being refused food by his son, the second Baronet, a group of starving Highlanders prophesied that his house would melt awa’. I’ve been examining the surviving Wardlaw documents that chart his rise in royal favour, and admiring the beautiful Chancery hand of the royal deeds signed by James I and Queen Anne, part of the collection donated to the Scottish Archives by Arthur Balcarres. Sir Henry acquired the lands of Pitreavie in 1608, and built a beautiful Renaissance mansion there. He was knighted in 1613, and in 1614 the Charter of Barony refers to him as predilectus servitor. He was granted a pension of ane thousand pounds Scottis for his service in managing the Queen’s regalia in Dunfermline and this may have been the occasion when he was presented with the gloves. The Queen died in 1618.

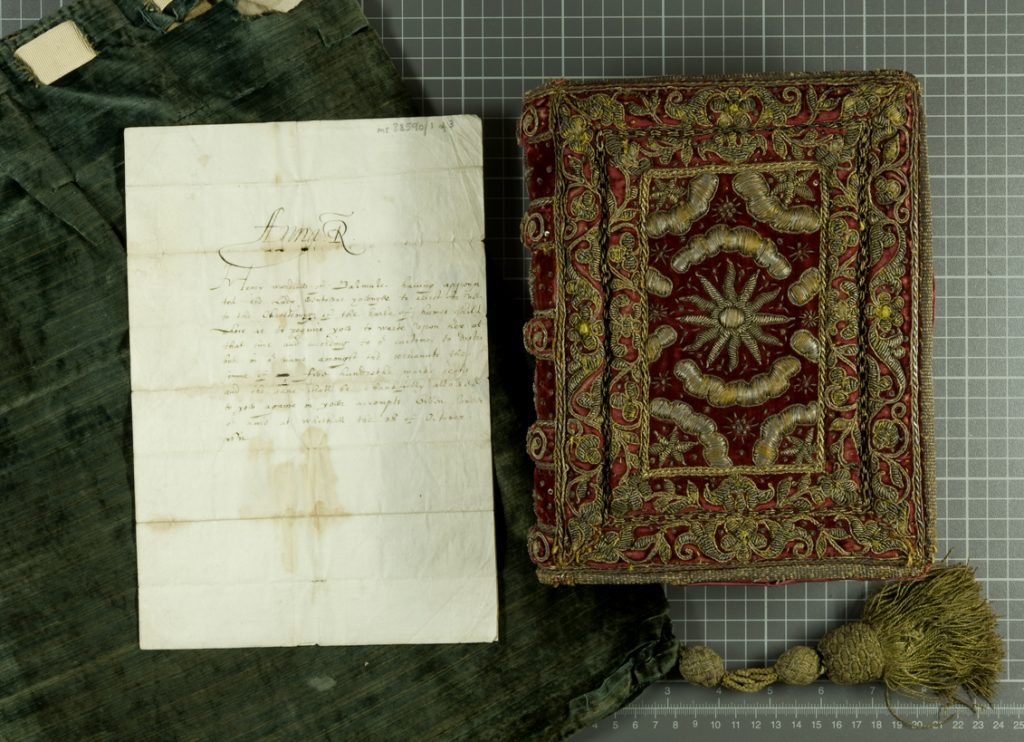

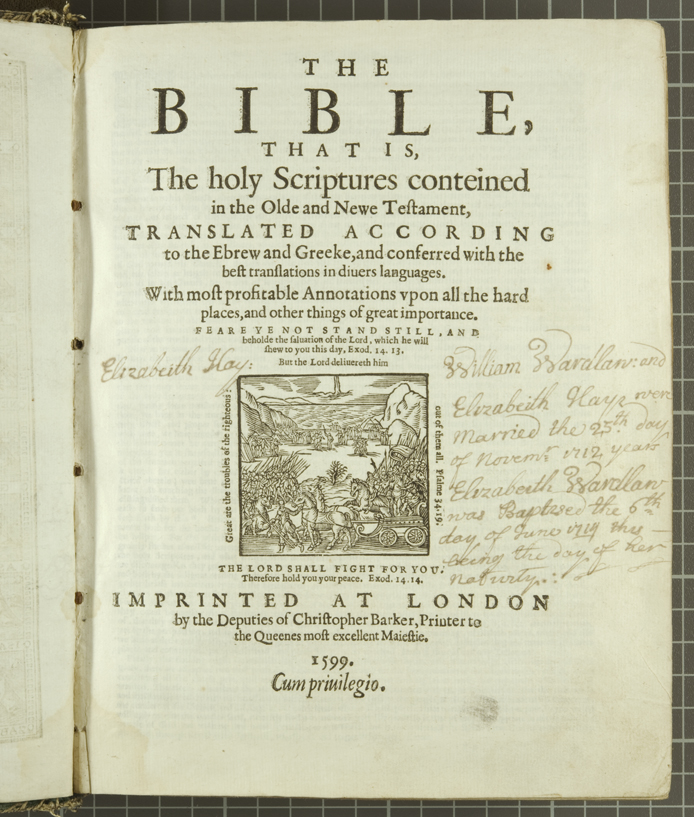

The Wardlaw treasures, a pair of gloves and a Bible, were presented at different times. The gloves are dated early 17th century; family tradition claims they were filled with gold coins and presented to Sir Henry by Prince Charles. As King, Charles referred to him in a letter as an “old and faithful servant to our late dear father and mother and unto us.” The Bible is a rare edition, bound with a psalter, both published in 1640, after Henry’s death. Henry was created a Baronet by Charles I on 5 March 1628, and the Bible in its gorgeous embroidered covers and satchel was probably presented to Henry’s son. A letter from Queen Anne accompanies the Bible. However, this letter is more likely to have been sent with the gloves, only to be stored inside the Bible for safekeeping at a later stage. We know that there was a letter from King Charles I inside the Bible which has been lost. The puzzle about the dates still needs resolving.

The embroidered cover to the Bible, with accompanying letter from Queen Anne.

Both the gloves and Bible were treasured by descendants of the Wardlaws, and were passed to the Wardlaw Ramsays when Captain Wardlaw married Elizabeth Balfour.

The traditional use of a Bible, to record family weddings and baptisms… How old was Elizabeth?

I’m amused to read that my grandfather was actively researching his Wardlaw ancestry to establish his position in regard to the Pitreavie baronetcy, failing heirs to Sir Archibald Wardlaw, the seventeenth Baronet. Dream on…

Two Ramsay portraits

This delightful portrait was acquired by the National Gallery of Scotland. It’s of Katherine Hall of Dunglas, and was painted in 1736, just before Allan Ramsay travelled to Rome to study the history of art. Now cleaned, its rosy colours contrast with Ann Ramsay’s darker image. Like other early portraits by Ramsay, both girls are shown in the same dress that can be seen in many of his paintings. As a journeyman artist, he would travel with prepared canvases, and simply add the sitter’s head to the bust. Ann’s portrait was painted prior to her marriage to Robert Balfour in 1736, so about the same time as Katherine’s. A good clean might transform her complexion!

Families by marriage

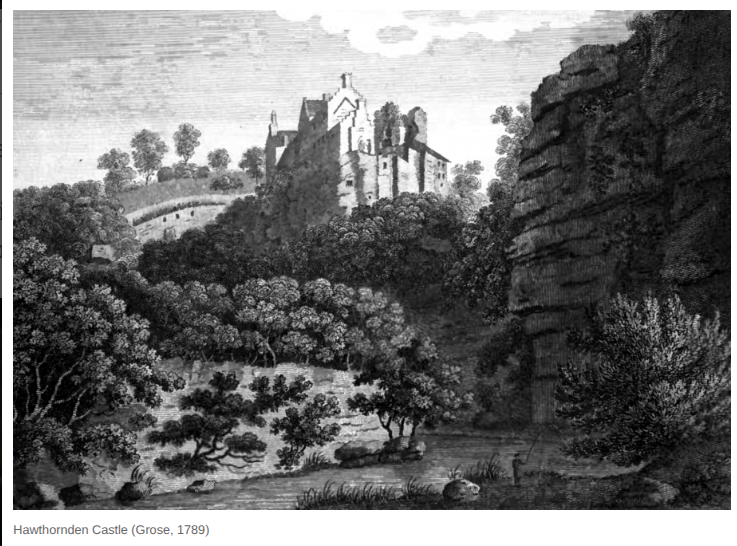

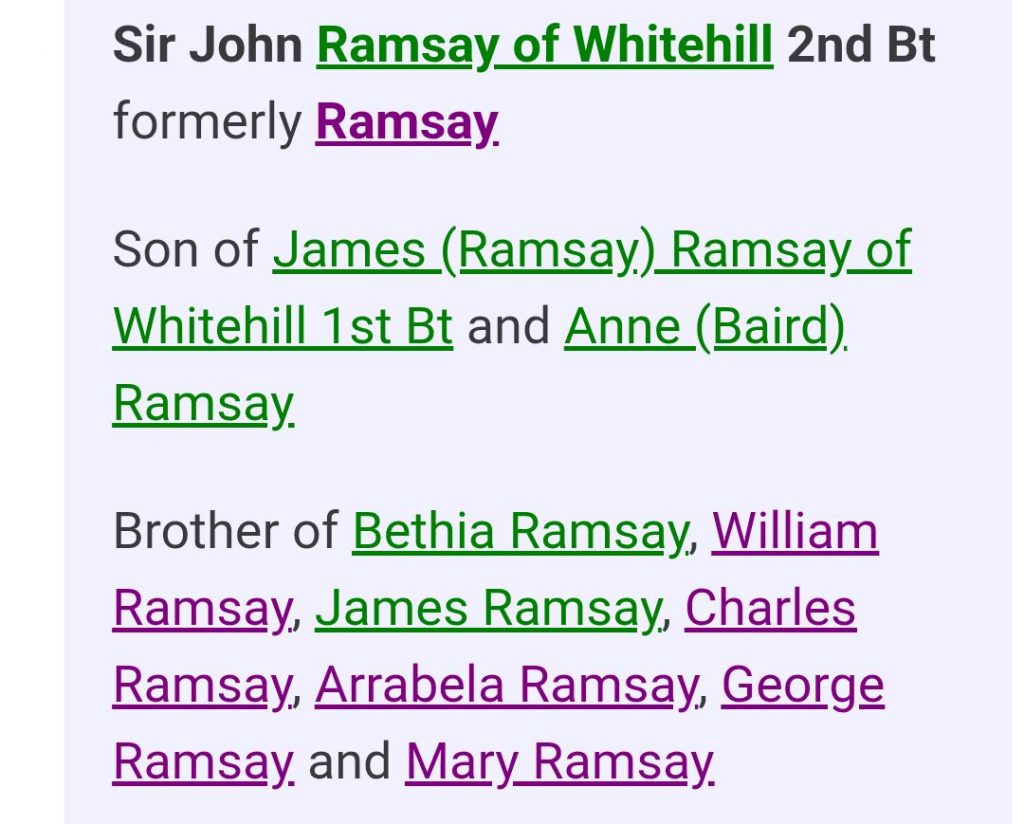

I’m interested in the family networks that influenced each successive generation of Ramsays of Whitehill. Our earliest portrait, Sir James Ramsay in full armour, harks back to an age of chivalry and status. How did his descendants fare? In 1671 his son, Sir John married Anna Carstairs of Elphinstone, in Carrington church. Her family lived in the Canongate. Her grandfather, also Sir John, had married twice and had many descendants. On her mother’s side, Anna was related to the Ainslies, a merchant family. A year after the marriage, Sir John and Anna sued her father for £20,000, promised to him if John Carstairs had no other children. The jury hummed and hawed and eventually said wait until one of her parents died. The father died 20 years later, after Sir John’s death. For her part, Anna died in 1689, having given birth to nine children, John 3rd Baronet, Isobel, George Ramsay, Andrew 4th Baronet, Margaret, Mary, and James, who died in infancy in 1680. That’s three families, the Ainsleys, Carstairs and Ramsays, all related through marriage. I fear that Sir John’s incurred yet further debt to find dowries so his girls could marry gentry. Isobel married William Drummond and went to live in Hawthornden Castle (the engraving below suggests that it had been improved with a Georgian front). Her sister Mary married Captain William Preston of Gorton, an ancient family which used to hold Craigmillar Castle, though it had passed out of their hands by William’s time. This record provides a glimpse of the families interacting:

2 January 1717: Letters of General Charge at the instance of Sir John Ramsay of Whitehill, Bt, Mr Andrew Ramsay, advocate, Mary Ramsay, daughter of deceased Sir John Ramsay of Whitehill, Bt, and Captain William Preston of Gourton [Gorton], her husband, against [blank] Wilkie now of Broomhouse, eldest son of deceased Mr John Wilkie of Broomhouse, and his other children, charging them to enter heirs to their said father. In dorso: Certificates of execution thereof, 8 and 18 January 1717. National Records of Scotland, Wilkie of Foulden Writs, reference GD59/141

This action was precipitated by the death of John Wilkie, but the older Sir John Ramsay had died in 1715, causing his debts to be called in. It doesn’t tell us where Mary and William lived (probably Edinburgh) but it is a reminder that it’s always been useful to have a lawyer in the family!

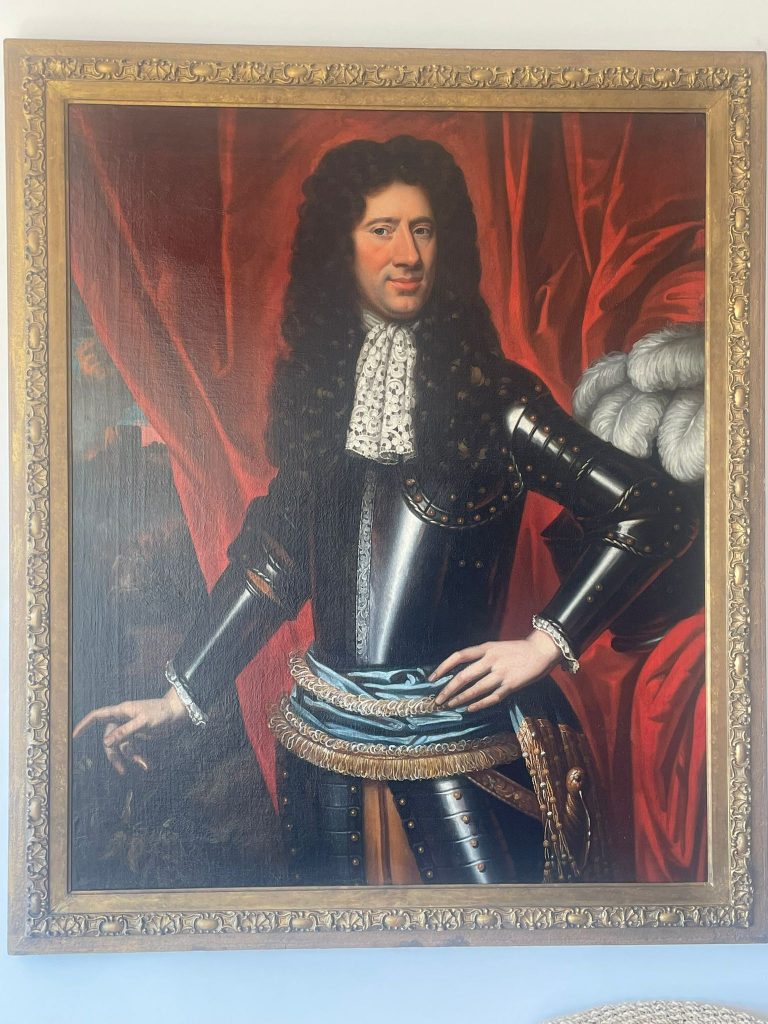

The copper cuirass

Admiring Sir James’s fine suit of armour leads me to take another look at his son’s breastplate. Sir Andrew’s appears to consist of overlapping copper scales, which begs the question of why he’s not wearing his granddad’s armour? Of course, it won’t have been in fashion and he was probably too big for it. I assume it had been sold to help pay off debts. The copper breastplate has a theatrical air, in keeping with Sir Andrew’s huge wig and painted smile, and may have been a studio prop. Scotland was reeling from the collapse of the South Sea Bubble, and the Hanoverian army was still engaging with Jacobite forces, after the 1715 uprising. The portrait is dated 1721, and marks his accession to the baronetcy. It is also the year Sir Andrew died, presumably as one of the many victims of the plague; 1721 saw the last and most devastating occurrence of this scourge. He left a widow and four children, two of whom survived to adulthood.

Cleaned portraits

It’s always a happy moment when an old portrait comes back from the restorer looking a million dollars! This is especially the case with our Sir James whose charismatic features have been revived, as he surveys the vicissitudes of the family he did his best to bankrupt! Medina charged about £10 for a half-length portrait, and this is one extravagance we are grateful for.

See below for Before and After versions! This portrait was probably bigger, and was cut down to match the other portraits when they were hung in the huge dining room at Whitehill House.

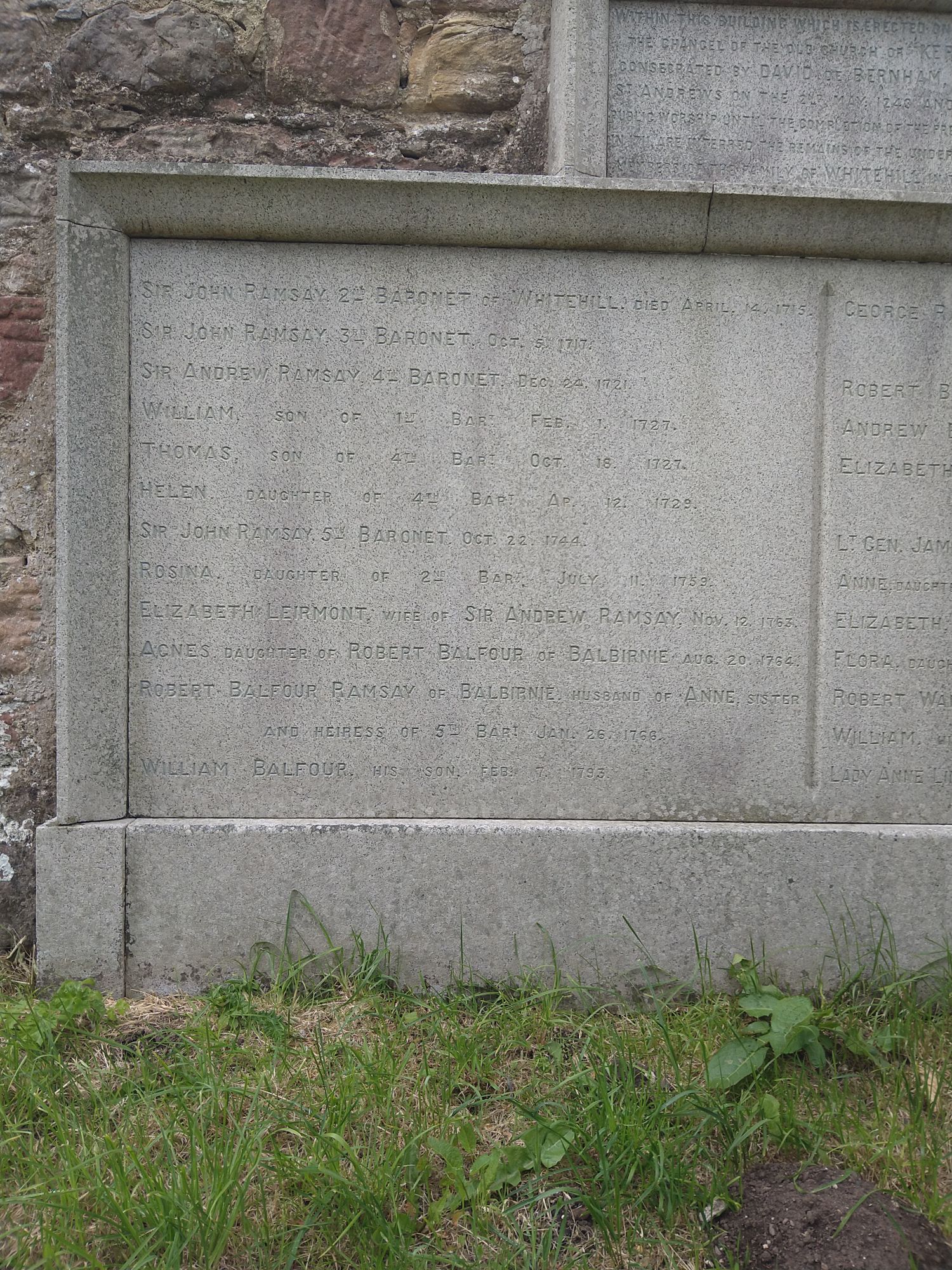

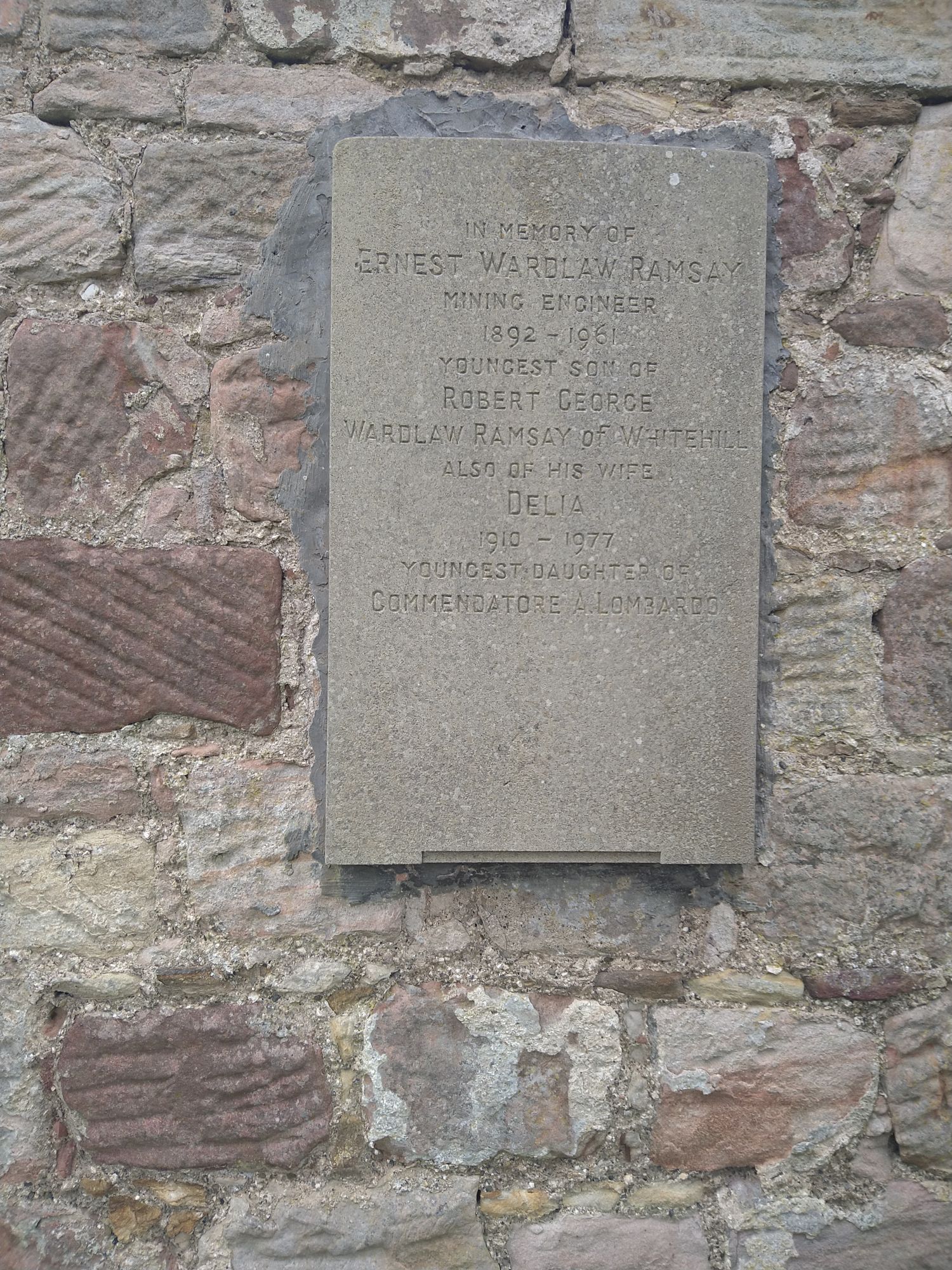

The Ramsay Vault

The medieval church was under Ramsay patronage, so deceased family members were presumably buried inside the church. Thus, when it was demolished in 1711, a mausoleum was erected on the site, presumably for re-intering recovered bodies. The first recorded burial is that of Sir John Ramsay 2nd Baronet of Whitehall, who died on 14 April 1715. Over time, a total of 22 coffins were added to the stone shelf within, and sporadic efforts were made to tidy up. The last person to be buried in the mausoleum was Lady Anne Lindsay, wife of Robert Wardlaw Ramsay, who died on 14 January 1846. Then, in the 1880s, the contents of the mausoleum were removed and buried in the little plot next door, and a stone plaque listing their names was attached to the side of the church. Subsequent Wardlaw Ramsays had their own gravestones, or plaques, inserted within the plot.

The Italian Connection

Whitehill Aisle – forgotten gem

The sun was shining as I walked along the newly-mown lane to the old cemetery. To my surprise, the whole area had been mown, exposing the splendid C18 headstones that survive. The Ramsay Vault is built from stones of the old church, most of which were removed to build the new church, in the village. The inscription on the vault reads: “This building…is erected on the site of the chancel of the old church of Kerington consecrated by David de Bernham, bishop of St Andrews on 2nd May 1243 and used for public worship until the construction of the present church in 1711.” Interestingly, the headstones are all later in date. Local people clearly felt attached to the old site. Surely, it’s time for a proper gravestone survey.

18th century monuments

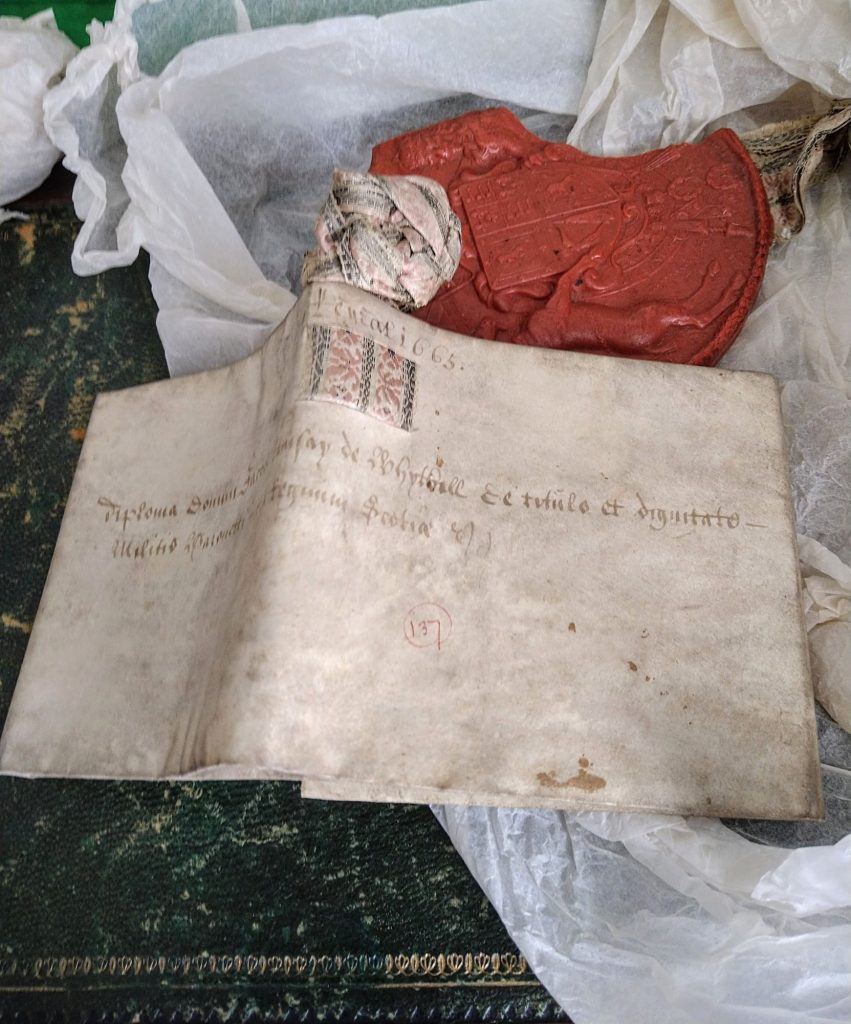

Knight Baronet, the costs…

First, James arranged to borrow 3000 merks from William Robertsone of Edinburgh (Bond dated 20 August 1664) to pay the fee. When the Patent was awarded the following year, James paid John Teller “Masmad” alias Roxburg herald 200 merks as herald’s due. Then, £60 Scots to the Gentleman Usher for organising the investiture ceremony. A further 40 merks to Alexander Ferguson, one of the 5 trumpeters for the fee due to them for “the honour and dignitie as knight and baronet…”, together with 80 merks fees to the macers of H.M. Privy Council and Exchequer. And that was just the participants in ceremony. There were the court clothes, and commissioning a portrait of the new baronet in all his finery… The main debt lingered on…

By the 1670s, Sir James had so many debts that when he died in 1674 there was a rush to call them in. His sister Margaret had to hastily renegotiate the bond that was security for her house and stables in the Netherbow.

Younger sons!

Large families were ideal, given the high mortality rate. Male heirs were essential for preserving the baronetcy (purchased 1665) so younger sons were an important reserve. William Ramsay (right) was born about 1658, as younger brother to John, the second Baronet.

His nephew Andrew (left) inherited the baronetcy from his older brother, also John, when he died in 1717. George Ramsay, advocate, would have inherited but he had died earlier. The surviving portraits show a strong family resemblance, especially their noses!

It’s difficult to establish biographies for younger children. The girls marry and are subsumed into their husbands’ family histories. The boys enter professions, but the records are not complete. William was a Writer to the Signet and married Mr Hayes’s daughter in Edinburgh on 11 Jan 1690, at 8pm, in the Hayes home. The new couple was dead 3 months later; William’s portrait appears to have been preserved by his father.

The disappearing necklace

Who knew this necklace had a story to tell? First of all, it was discovered by the restorer, who removed a layer of flesh coloured paint that was covering it. That’s why it’s not very well defined. However, Lady Louisa’s bracelet and earrings are now revealed as parts of a grand parure.

Castellani was the fashionable jeweller who made them. It’s possible that Robert Wardlaw Ramsay bought the showy piece during a sudden journey to Lucca. Their oldest boy, William, had announced his engagement to a girl there, and Robert was determined to put a stop to this. He may have allowed himself a moment in the local jewellers to purchase this gift for his wife, back in Edinburgh with the two youngest boys. Why the necklace was later painted over is another story! The real parure disappeared long ago…

Major Ramsay, coalmaster (to read this sequence in order, scroll down to the 1789 General Defence blog)

A letter from Archibald Campbell dated Wednesday morning lands in Whitehill, reminding Major Ramsay that his Grieve has delivered only 2 carts of coal to Balburnie, instead of the half dozen promised. They are worried that if a storm comes “we shall be in a scrape”. Any quality of coal will do, but please send more!

This letter casts some light on how Major Ramsay was running the coalworks in Fife (Dundonald) as well as Whitehill, and supplying the senior Balfour family home in Fife with coal. Dependence on coal for heating and local industry was well entrenched by the end of the 18th century, and Balburnie was already a big place.

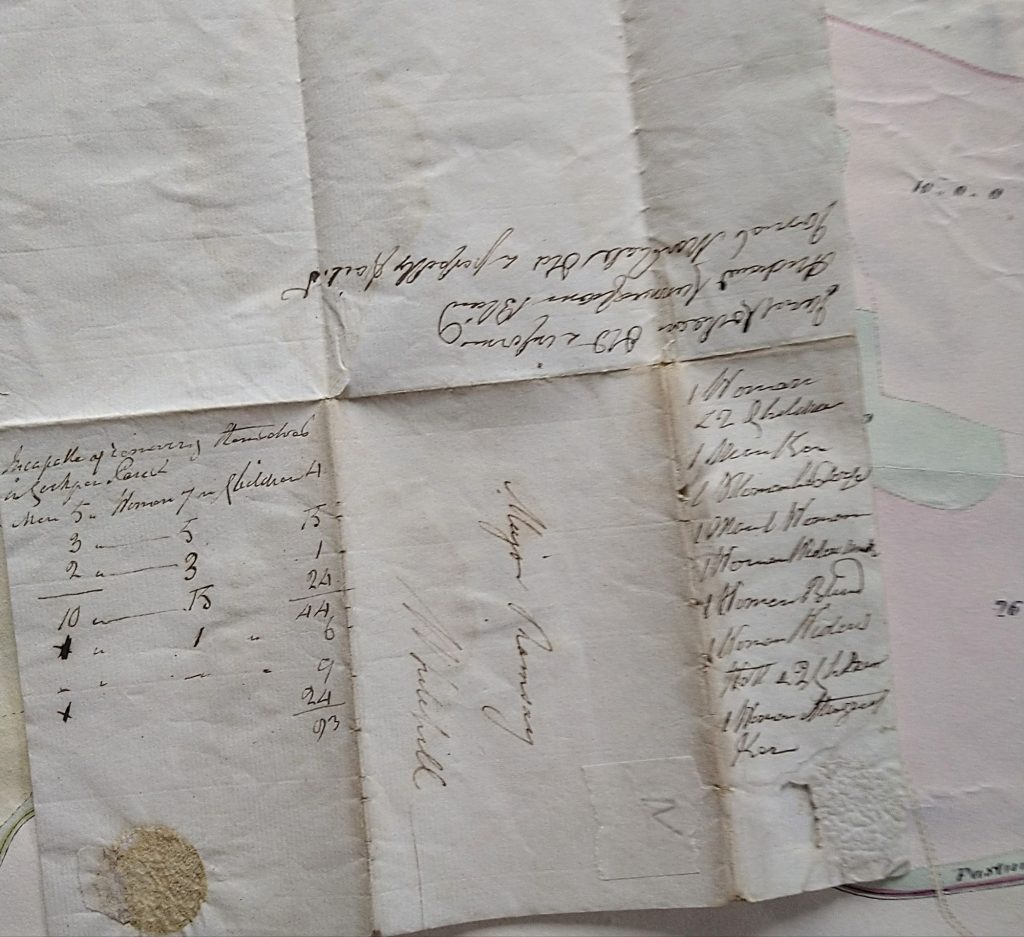

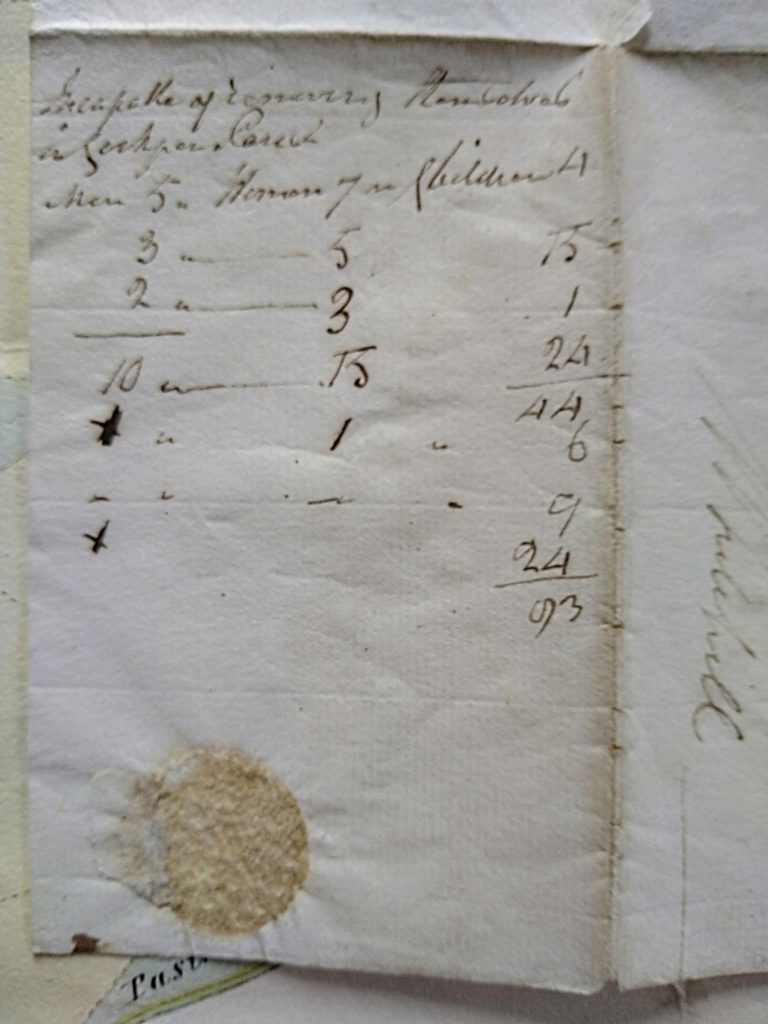

Ramsay must have had this letter in his pocket as a reminder, as he used it to jot down calculations about the number of infirm persons in Cockpen parish who would require transport to evacuate them in the event of an invasion. Maybe the preparations for an invasion had put pressure on coal supplies.

Widows, babies and the blind

The defence strategy adopted in 1798 was to present the invaders with a desolate hostile landscape, empty of people, animals, houses and crops. The Pioneers were instructed to destroy ovens, roofs, roads, and bridges. Hence the interest in the number of carts available for evacuation purposes. A list scribbled by Major Ramsay on the back of a letter shows his concern.

Ten vulnerable women, widows, blind, infirm, or with small children, and two men are cited. He tots up the final numbers of those “incapable of removing themselves in Cockpen Parish”, and the figures are stark: 12 men, 16 women, and 93 children.

How many carts would they require, and where would they go?

Thankfully, the French invasion never reached Scotland, and the Major’s logistical skills were not put to the test.

However, the schedules provided the government with a great deal of information. One effect was to establish links between villages and recruitment sergeants. This had enduring consequences for communities in Midlothian, and Scotland generally.

The village schoolmaster

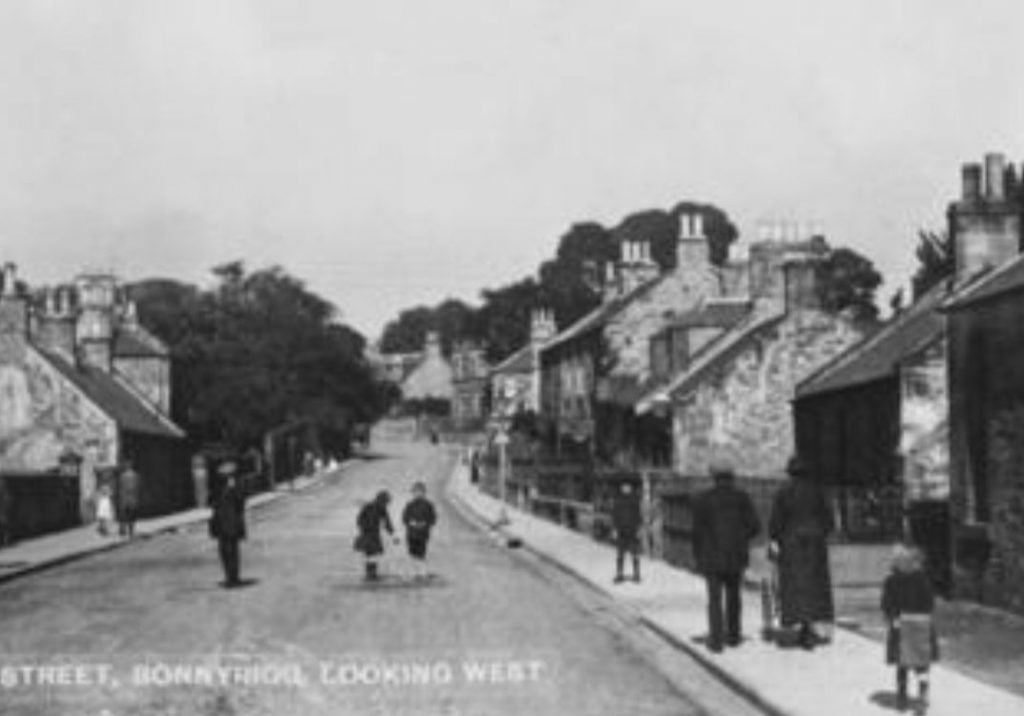

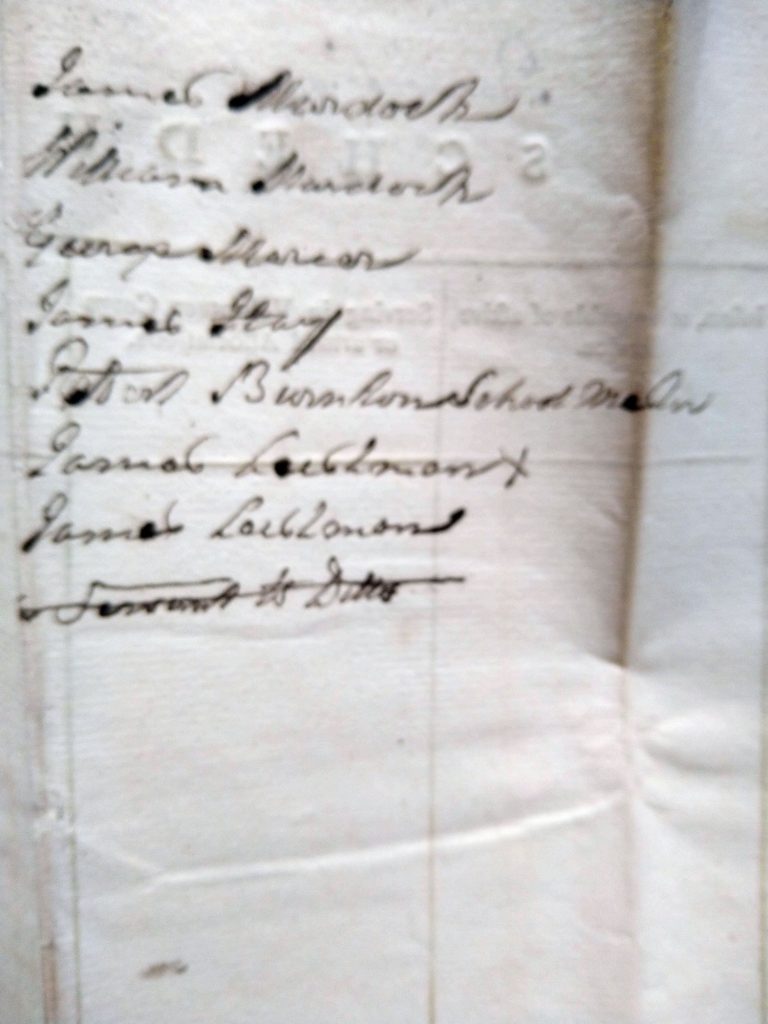

We meet all the adult male inhabitants of Bannockrig in one schedule. The list features 52 names, many of them related. For instance, the first three entries cite Andrew, John and Robert Philip. So we can assume that there were ca 25 households in the village (now known as Bonnyrigg).

The Schoolmaster, Robert Burnston, may have had at least 40 pupils to teach. Indeed, Bonnyrigg boasts an old schoolhouse, possibly on the site of Mr Burnston’s classroom.

With no other details to go by, we can assume that these men (with the exception of Mr Pollard who was infirm), would have turned out for training in arms when the sergeant arrived.

The innovators

We’re told that agricultural labour relations were changing radically at this time. Farms were being reorganised into larger divisions, tilled by servants, many of them single men.

The schedule for the estate farm at Dalhousie Mains provides a snapshot of this change. The farm belongs to the Marquis of Lothian, and comprises 11 men, most of them unmarried as only 2 infants present. So, they are farm labourers, housed inside the farmhouse.

The list of crops reveals an astonishing 300 bolls wheat. The total land under plough is 420 Scottish acres (bolls), not including 4 acres of potatoes and 400 stones of hay (poss. 2 acres) This is a mega farm, and the farmer surely needs extra hands to work it. Boll wages for unmarried ploughmen were £5; £7 for married men. Women could earn £2.50 and day labourers 10 1/2 pence a day.

The livestock includes 72 cows, 173 sheep, 54 pigs, and 7 riding horses, requiring further farm workers.

The next schedule lists two large farm (near Newbattle, so also belonging to the Marquis of Lothian?) that, together, are growing 747 acres of wheat, in all over 1000 acres. Managed by an army of 197 farmworkers, using 4 oxen, 96 draft horses and 45 carts. 24 of the men are employed in local industries. At least 50 are married, and housed in bothies around the estate: 85 children are listed under ‘Persons incapable of removing themselves’.

This cohort of farmworkers and labourers supplies 42 infantry recruits, and 36 pioneers.

Large farms, with large workforces were the way land was being managed, now. In the next century, women would supply much of the farm labour as the men took the heavy industrial jobs. All this wealth creation (mines and mills included) helped finance the construction of country houses in Midlothian, as well as significant home improvements, such as at Dalhousie, Whitehill and Newbattle.

Small farmers –

Two schedules provide information about small farmers. One lists a group of 14 men, who include 5 Wilsons and 2 Ramages, living on 6 farms. Each farm has a cow (Alex Ramage has 5). 4 farms keep 2 or more horses (A.R has 4 horses and 3 carts). Thomas Lishman and John Wilson both farm at Burnhead and between them have 7 horses and 7 carts. The inference is that this group of farmers is providing a carrier service to local industries and farms. Are they the remnants of freehold farmers, who have retained their status but are now providing day labour to survive? Three of these men came forward to serve as volunteers.

The other schedule is devoted to John Goodman (age 44) who lives with his wife and family on a farm that boasts 1 ox, 3 pigs, 2 draft horses. He has sowed 4 bolls oats, 4 bolls barley, 1/2 boll potatoes, and 7 pecks potatoes, as well as hay. This farmer has no servants, and is clearly well able to provide for his family. No volunteers for training in arms, here!